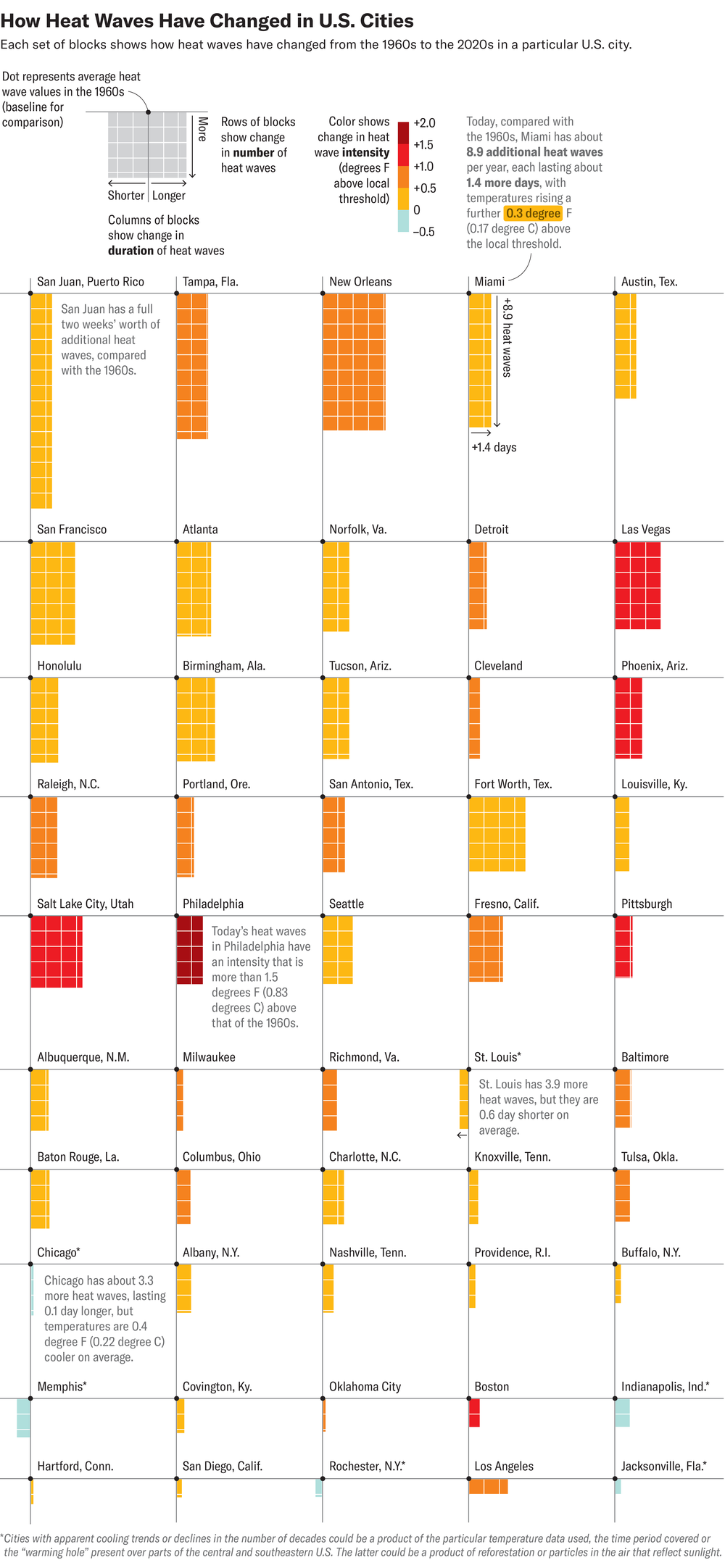

Children growing up in Philadelphia today experience more than four more heat waves every summer than those who grew up there in the 1960s. Kids in San Francisco today endure nearly seven more heat waves per year than their counterparts in the mid-20th century did. And in New Orleans children are currently subjected to nine more.

Exactly how many heat waves hit any city in a given summer has always been subject to the whims of the weather. But is very clear that—with global warming now heating the world to 1.2 degrees Celsius above its average in the late 19th century—summers are dramatically ramping up. “There’s no question that summers have changed,” says Kristie Ebi, an epidemiologist who specializes in heat-related health risks.

In short: The milder summers of our parents and grandparents are a thing of the past.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Today’s summers on climate change steroids are not just a matter of shirts increasingly clinging to sweat-drenched backs or individuals needing to crank up the air-conditioning more often. They pose a major and deadly public health threat that people, cities and countries are only beginning to grapple with. Record-shattering heat waves last summer—the hottest in the past 2,000 years—underscore the growing danger. Some 2,300 people in the U.S. died from excessive heat during that season, the highest number in 45 years of recorded data, according to a recent Associated Press analysis of data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And some experts say that record only counts a fraction of the true number of heat-related deaths.

This summer is very likely to bring more of the same. Though it is impossible to say where and when any specific extreme heat waves might take shape more than a few days ahead of time, the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service’s forecast shows a greater than 50 percent chance of above-normal temperatures across nearly all of the Northern Hemisphere. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration also predicts above-normal temperatures for most of the U.S., especially the Southwest and Northeast. The high odds of a hot summer in those areas are primarily based on the long-term global warming trend, notably in the Southwest, says Dan Collins, a meteorologist at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center. In “this season and that region, the trends are particularly strong,” he says. And these predicted temperatures are measured against a baseline of “normal” readings from 1991–2020—when global warming’s impact was already becoming measurable—meaning this summer is even hotter when compared with those that occurred earlier in the 20th century.

So far these forecasts are proving accurate. A major heat wave developed over the western U.S. early in June, sending temperatures soaring to levels more typical of those later in the season. That same dome of heat had been roasting Mexico since the beginning of May, breaking records and causing howler monkeys and birds to drop from trees after dying of heat stroke and dehydration. A heat dome is bringing potentially record-breaking hot temperatures to the eastern half of the U.S., especially New England, in mid-June. Outside of North America, broad areas of Asia—from Gaza to Bangladesh to the Philippines—sweltered in climate-change-enhanced heat during April and into May. These events show how summer heat is bleeding into spring, as well as into autumn.

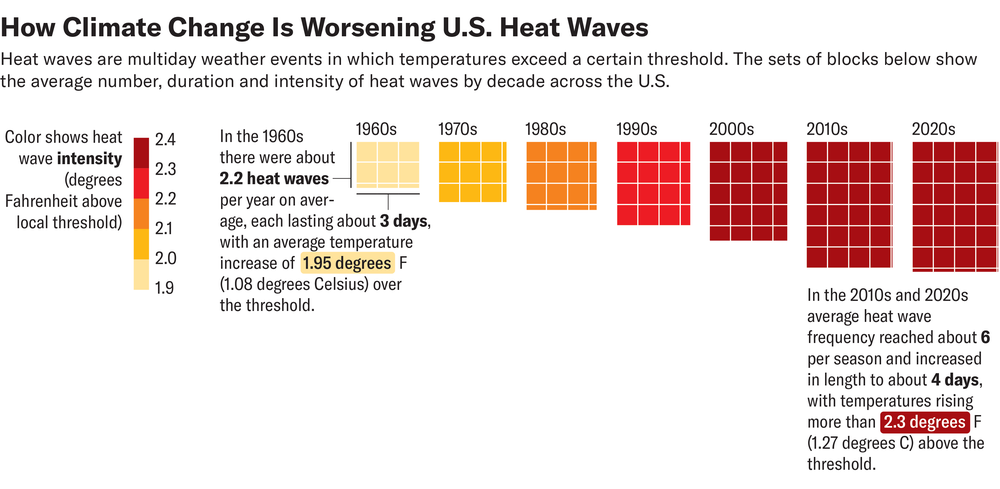

Amanda Montañez; Source: Climate Change Indicators: Heat Waves, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (data)

The shifting character of U.S. summers can clearly be seen in data charting extreme heat events in 50 major cities. Such events are defined as temperatures reaching the top 15 percent of local records because what qualifies as extreme heat differs in, say, Houston and Seattle. Based on the trends seen in those data, on average, U.S. residents have gone from experiencing two heat waves each summer in the 1960s to more than six today—and the duration of those heat waves has lengthened from three days to four. The heat wave season also lasts much longer, extending from just more than 20 days in the 1960s to more than 70 now. Changes in heat wave characteristics for individual cities can be seen in the graphics below.

Amanda Montañez; Source: Climate Change Indicators: Heat Waves, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (data)

These trends can have far-reaching health consequences: people aren’t always prepared for today’s extreme heat because we think of summer weather in terms of a gentler climate that no longer exists. “Prior experience is so important,” says Micki Olson, who researches risk communication at the University at Albany. “It’s a big influence in how people perceive the risk.” And even when individuals do remember heat waves and how they were affected by them, “they remember a heat wave—they don’t remember a temperature,” Ebi says. This means people don’t always know what temperatures call for special precautions or what those precautions might be.

The deadly nature of heat is also not well recognized by the public. Heat waves are the deadliest extreme weather events in the U.S., killing more people than hurricanes, tornadoes and floods combined. But this is an invisible threat that unfolds over many days, Olson says, unlike a roaring funnel cloud or the rushing wall of an ocean storm surge. And the death toll of a heat wave is often unknown for weeks or months, making it difficult for people to connect the event to the inherent risk.

Olson’s research has shown that it’s difficult for the pubic to grasp the exact meaning of measurements such as the heat index (which factors in both the temperature and humidity) or the National Weather Service’s (NWS’s) heat advisories and warnings. New efforts, including a “heat risk” ranking rolled out by the NWS this year, provide more information about what the risk levels are and when precautions need to be taken. But it is not always clear which populations need to be alert to what rankings, Ebi says. For example, those who are age 65 and older or are otherwise highly vulnerable need to be concerned even amid a “minor” risk ranking.

As summer heat becomes a growing threat, meteorologists need more help in spreading the message about risks and precautions, Ebi says. For example, pharmacists can let people know if a medication reduces the body’s ability to sweat, thus making an individual more susceptible to heat illness. Adapting will also require rethinking where and how we build: Many homes in places like Seattle often lack central cooling because it wasn’t needed in the past. “Areas that didn’t have air-conditioning will need air-conditioning,” Olson says. A few U.S. cities, including Los Angeles and Phoenix, have created a “heat officer” position to better spread awareness, recommend more specific precautions (such as how much water people in at-risk groups should be drinking and how often they should consume it) and coordinate services with organizations that work with unhoused populations.

Such concerted efforts will become increasingly necessary: as bad as it is already, summer heat is only going to intensify. A 2021 study in Science found that, under countries’ current greenhouse gas reduction pledges, children born in 2020 will experience seven times as many heatwaves over their lifetime as people born in 1960. Those future waves will also last longer and feature ever higher temperatures than today’s.

Aggressive climate action can avert that scenario and make future summers more tolerable for our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. But even if those countries’ commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are strengthened so that global temperature rise is limited to 1.5 degrees C above preindustrial levels, the 2020 cohort will be subjected to four times as many heat waves as the 1960 one.

As Ebi told a class of college students during a lecture last year, “When you get to be as old as I am, you’re going to look back and think about how nice the summers used to be.”