People on the East Coast earlier this month experienced something that occurs with relative frequency in the West: ominous orange skies lit up by dense wildfire smoke. Across the I-95 corridor they responded with many important questions: How bad is the air quality where I live? Can I exercise outside? When will the smoke go away?

Many Americans, especially throughout the wildfire-prone West Coast—where climate change is making the infernos worse—are all too familiar with these questions and seek answers from smoke-tracking tools like the AirNow Air Quality Index. But these tools are only as good as the data that go into them. Currently, the index is based on an extensive network of more than 1,000 monitors run by state and local environmental agencies.

That may sound like a lot, but each of these monitors only measures air quality at a single point in space and time. The lower 48 states span over three million square miles, leaving a lot of air between monitors.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

We can and must do better.

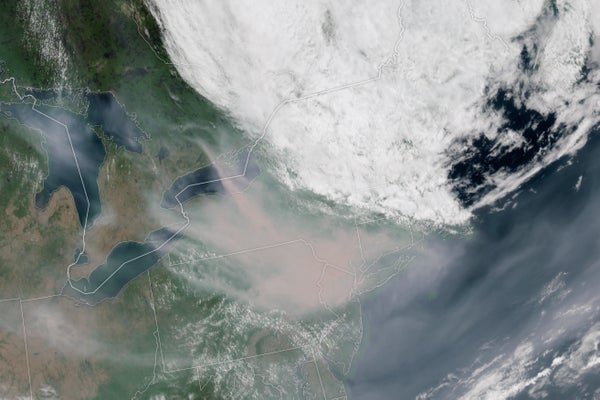

A new generation of space-based satellites is capturing images of smoke and taking measurements of pollution in the Earth’s air with much greater coverage than monitors on the ground can manage. So far, most of these satellites orbit the planet once or twice per day, taking a snapshot of each location on Earth in the early afternoon at each pass. This past April, NASA launched TEMPO, the first air quality-observing satellite that will stay in a fixed position above the U.S. as the planet spins, enabling it to take pictures of the Earth’s air during all daylight hours. TEMPO joins the Geostationary Observational Environmental Satellite, GOES-R, which provides a continuous record of weather, smoke and dust over the U.S. from coast to coast. This month, GOES imagery tracked the Canadian wildfire smoke as it flowed from Quebec to the U.S. East Coast, driven by the stagnant low-pressure system over Nova Scotia.

Scientists are hard at work combining information from satellites and monitors on the ground to provide relevant and timely air quality information everywhere across the U.S. Both of these smoke monitoring tools are imperfect, but each contributes valuable information to understanding the impact of wildfires on U.S. air quality. Ground monitors provide direct measurements of harmful pollutants in smoke plumes at the “nose level” where we breathe. Satellites fill in the large spatial gaps between monitors to provide air quality information for everyone across the U.S., even those living far away from a monitor. Satellites also provide crucial information on fire locations and upwind pollution needed for forecasting where the smoke will go and how bad pollution levels will be.

Surveys show that people take action to avoid pollution exposure during smoke events. Sometimes, this means evacuating the polluted area. More often, people decide to stay indoors or wear a mask to reduce their exposure. Just like weather forecasts, air pollution predictions provide actionable information to the public. Since wildfire smoke is associated with respiratory and cardiovascular disease, among other illnesses, accurate and timely smoke forecasts can actually save lives.

Supplementing ground monitors with satellite observations provides more detailed data for air quality alerts, equipping people with better information to protect themselves. As our research shows, people taking action to reduce their exposure during air pollution events, including those caused by wildfires, could avoid nearly 3,000 premature deaths nationwide each year. This is only scratching the surface of the usefulness of air quality data from satellites for protecting public health. We have tracked air pollution disparities, air pollution sources and changes in air quality over time with satellite data, for example, in our own research.

Despite their enormous value added in filling in the spatial gaps between monitors, satellite data records are not guaranteed to continue. Satellites age, fall into disrepair and are decommissioned over time. The new TEMPO satellite’s primary mission is only 20 months long. Though scientists hope it will keep working for years beyond that, satellites must be planned years in advance to ensure that life-saving data records continue beyond the missions now in operation.

Fortunately, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is planning a new satellite mission, GeoXO, to take over from TEMPO and provide hourly air quality measurements across the U.S. Inevitably GeoXO is facing a gauntlet of technical, political and budgetary decision-making that will determine its future. Yes, satellites are expensive. GeoXO’s total program life cycle cost is $19.6 billion. But our research shows that the reduced mortality and illness achieved by equipping people with high-quality air pollution alerts could be valued at over $10 billion per year. Over the expected lifetime of the satellite, the health benefits greatly outweigh the costs. The health savings are also likely to grow as the smoke levels we experienced this month become more common under climate change.

High-quality, spatially complete air quality information helps people protect themselves during smoke episodes. With the resulting public health benefits in mind, GeoXO and other Earth-observing satellites are a bargain.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.