Multiple rounds of storms tore through parts of Illinois and Missouri in the first week of July, triggering widespread power outages that left tens of thousands of people without electricity—some for days after the storms had passed. It was just one of many such events to hit people around the U.S. this year. Government data show that blackouts are worsening in number and duration, and a new study shows they disproportionately affect already vulnerable communities.

For some, power outages are a mere annoyance: they can’t charge their phone, the food in the fridge may go bad, and their remote work may be affected. For others—particularly the elderly, those with preexisting health conditions or those living in poorly insulated homes—power outages can quickly lead to heat illness or hypothermia and even death.

A recent study published in Nature Communications finds that some U.S. areas with highly vulnerable populations are particularly prone to frequent and prolonged power outages. And data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) show power outages are happening more often and lasting longer. The researchers behind the new study—the first of its kind to analyze power outages on a county level—say that understanding where vulnerability and outages coincide can help utility companies and government officials prioritize resources when a power outage happens.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

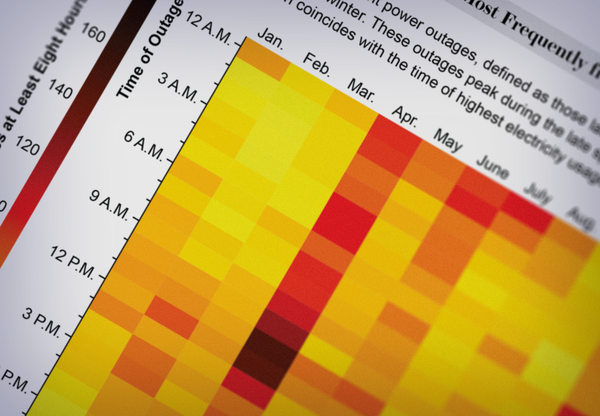

Credit: June Kim; Source: Reliability Metrics of U.S. Distribution System, U.S. Energy Information Agency

Between 2013 and 2021, the average duration of a power outage in the U.S. grew from approximately 3.5 hours to more than seven hours, according to EIA data. The frequency of outages increased from 1.2 to 1.42 events per customer per year.

Several factors—including climate change—contribute to these trends, says the new study’s senior author, Joan Casey, an environmental epidemiologist at the University of Washington. “Extreme weather is the number one driver of power outages,” she says. “As it gets wetter and the weather becomes more extreme, we can expect more power outages.” The aging electrical grid and insufficient funding for repairs also play significant roles in prolonging outages, she adds.

By analyzing county-level power outage data from 2018 to 2021, the study authors found that heavy precipitation was the predominant weather event linked to power outages (though they said their study could not specify a direct causal link between the two). The highest frequency of outages was observed from April to August. Power lines are prone to sagging from extreme heat during the summer months, and an increased number of people using air conditioners can also strain the electrical grid.

The study authors were particularly interested in power outages lasting more than eight hours, which are considered “medically significant” because they surpass the battery lifespan of most electrically-powered medical equipment and can leave people without essential air conditioning or heating for an extended period. The authors cross-referenced those outages with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), a classification system that pulls together information such as a community’s poverty levels and access to transportation. This helped the researchers identify where people are less able to withstand weather disasters.

They found that Louisiana, Arkansas, central Alabama and Northern Michigan were among the most vulnerable areas in terms of both SVI and power outages. “The states down by the Gulf [of Mexico] experience tropical cyclones and high winds that cause power outages and also have high social vulnerability,” Casey says.

Identifying the areas most affected by power outages can help utilities better serve customers in need and prevent any adverse health consequences. Lead study author Vivian Do says doing so requires a two-pronged approach: prevention and response.

Do, a Ph.D. student at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, emphasizes the importance of preventing outages from the outset. This involves strengthening the electrical grid by, for example, weatherizing electrical transmission lines to better deal with extreme weather and prioritizing vulnerable communities in the process.

In terms of responding to outages, Do underscores the significance of creating community spaces, particularly in rural areas, equipped with backup generators. Such centers could offer charging stations for phones and computers, as well as heating or cooling facilities.

Organizers in parts of Louisiana have launched initiatives to help those vulnerable to blackouts. A coalition of local groups in New Orleans have started the Community Lighthouse Project, which is aimed at setting up dedicated spaces where residents can recharge their devices and get access to crucial resources during a power loss. These centers will be outfitted with solar panels and storage systems to ride out breakdowns in the wider power grid.

Such initiatives have the potential to not only help communities with disaster response, but also to address the broader social and racial inequities involved. “Low-income Louisianans and people of color are disproportionately affected by power outages,” says Jackson Voss, climate policy coordinator at the Louisiana-based nonprofit Alliance for Affordable Energy (AAE). Voss, who was not involved in the new study, highlights disparities in infrastructure investment by utility companies as a contributing factor. He adds that climate-friendly solutions—such as weatherizing homes—can soften the impact of inevitable blackouts, providing residents with better protection against extreme outdoor temperatures.

It is also essential to have a comprehensive plan in place for people who need to use electric medical equipment, says Eric Cote, project director at Powered for Patients, a nonprofit organization that assists patients in health care facilities during outages. He collaborates with various medical associations and state agencies to develop a process that helps local officials identify and allocate additional resources to the most critical oxygen-dependent patients, who need ready access to backup power sources, such as emergency generators or multiple sets of backup batteries. A detailed evacuation plan can also be helpful. “If someone who uses an electric wheelchair doesn’t have enough battery for it, that person must need help to evacuate,” Cote, who was not involved in the new study, says. “The types of challenges people face are different depending on the types of devices they use.”

Given the record-breaking temperatures increasingly occurring around the U.S. in summer, ensuring access to reliable power is increasingly becoming a matter of life and death. “What’s going on with the heat waves in Texas and the South is particularly difficult,” Do says.

Casey echoes these concerns and notes the inevitability of climate change bringing hotter temperatures and more extreme weather events. “If we don’t change the way we produce electricity or improve our grid, we will for sure see more power outages in the future,” she says.

On the other hand, “if we move to a more distributed power grid where communities produce more local energy and have local storage of that energy,” she adds, “that would improve grid resilience and community resilience in the face of these extreme weather events.”

WATCH THIS NEXT