The following essay is reprinted with permission from The Conversation, an online publication covering the latest research.

As the weather warms, people spend more time outdoors, going to barbecues, beaches and ballgames. But summer isn’t just the season of baseball and outdoor festivals – it’s also lightning season.

Each year in the United States, lightning strikes around 37 million times. It kills 21 people a year in the U.S. on average.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

For as often as lightning occurs – there are only a few days each year nationwide without lightning – there are still a lot of misunderstandings about nature’s largest spark. Because of this, a lot of people take unnecessary risks when thunderstorms are nearby.

I am a meteorologist who studies lightning and lightning safety, and a member of the National Lightning Safety Council. Here are some fast facts to keep your family and friends safe this summer.

What is lightning, and where does it come from?

Lightning is a giant electric spark in the atmosphere and is classified based on whether it hits the ground or not.

In-cloud lightning is any lightning that doesn’t hit ground, while cloud-to-ground – or, less commonly, ground-to-cloud – is any lightning that hits an object on the ground. Cloud-to-ground lightning accounts for only 10% to 50% of the lightning in a thunderstorm, but it can cause damage, including fires, injuries and fatalities, so it is important to know where it is striking.

Lightning occurs when rain, ice crystals and a type of hail called graupel collide in a thunderstorm cloud.

When these precipitation particles collide, they exchange electrons, which creates an electric charge in the cloud. Because most of the electric charge exists in the clouds, most lightning happens in the clouds. When the electric charge in the cloud is strong, it can cause an opposite charge to build up on the ground, making cloud-to-ground lightning possible. Exactly what initiates a strike is still an open question.

When and where does lightning happen?

Lightning can happen any time the conditions for thunderstorms – moisture, atmospheric instability, and a way for air to rise – are present.

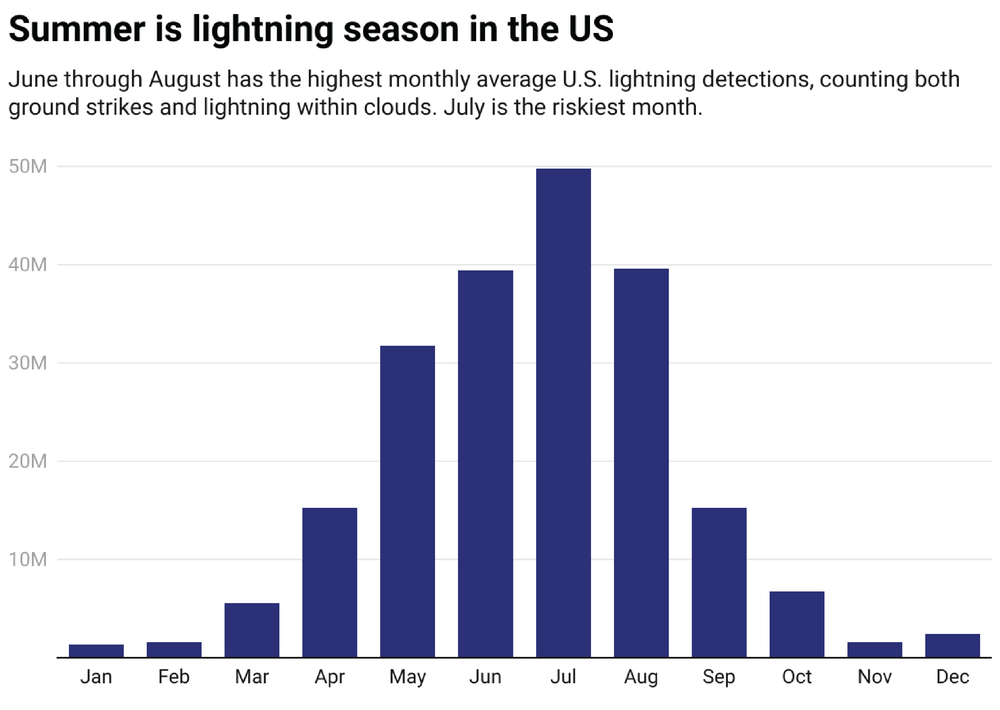

There is a seasonality to lightning: Most lightning in the United States strikes in June, July or August. In just those three months, more than 60% of the year’s lightning typically occurs. Lightning is least common in winter, but it can still happen. About 2% of yearly lightning occurs during winter.

The Conversation (CC BY-ND); Source: National Lightning Detection Network

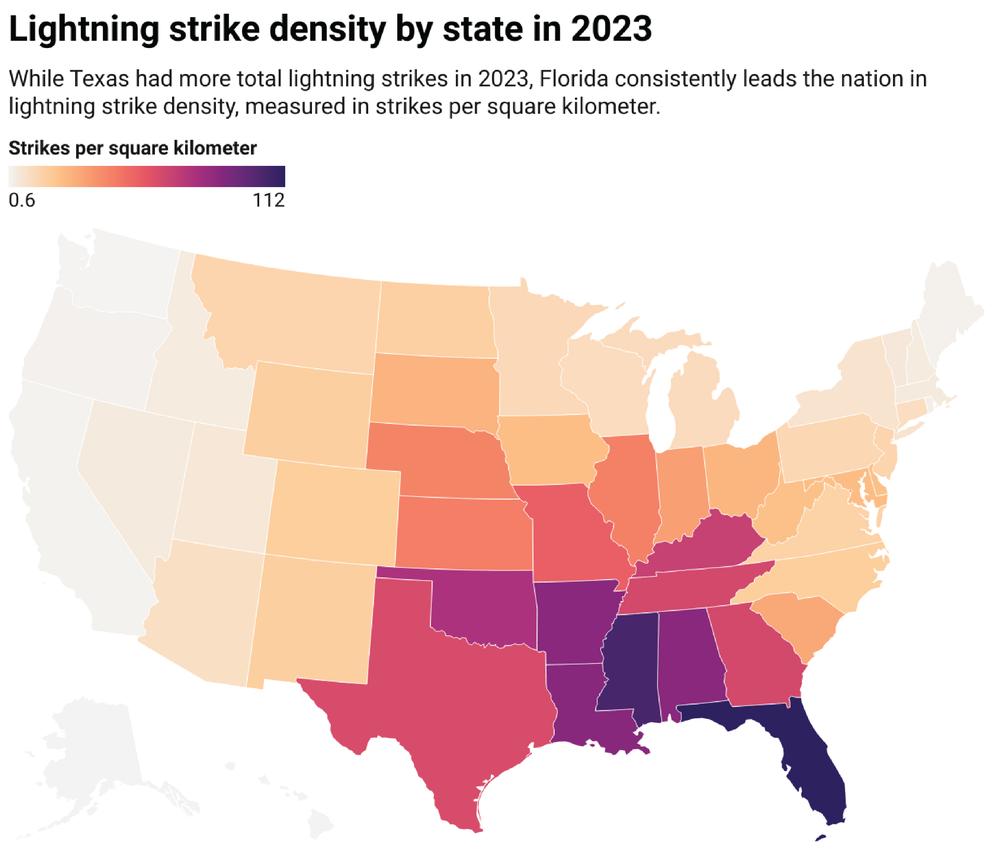

No state is immune from lightning, but it is more common in some states than others.

Texas, Florida, Oklahoma, Louisiana and Mississippi are often among the leaders in total lightning strikes, but more than 30 states regularly see at least 1 million in-cloud and cloud-to-ground lightning events each year.

How to stay safe from lightning

Almost three-quarters of U.S. lightning fatalities occur between June and August. Luckily, staying safe from lightning is easy.

Keep an eye on the forecast and reconsider outdoor plans if thunderstorms are expected, especially if those plans take you near the water. Beaches are dangerous because lightning tends to strike the highest object, and water is a good conductor of electricity, so you don’t want to be in it.

Remember: No place outside is safe during a thunderstorm, so when thunder roars – go indoors. When you see the clouds building up, hear thunder or see a flash of lightning, it’s time to dash inside to a lightning-safe place.

The Conversation (CC BY-ND); Source: Vaisala/XWeather

What is a lightning-safe place?

There are two safe places to be during a thunderstorm: a substantial building or a fully enclosed metal vehicle.

A substantial building is a house, store, office building or other structure that has four walls and a roof, and where the electrical wiring and plumbing are protected inside the walls. If lightning strikes the building or near it, the electricity from the lightning travels through the walls and not through you. Dugouts, picnic shelters and gazebos are not safe places.

If you’re in a fully enclosed metal vehicle during a thunderstorm and lightning strikes, the electricity travels through the metal shell, which keeps you safe. It’s not the rubber tires that protect you – that’s a common myth. So, golf carts and convertibles won’t keep you safe if lightning strikes.

When you’re outdoors and lightning approaches, head to a lightning-safe place, even if it’s a distance away. Stay away from trees, especially tall and isolated ones, and don’t crouch in place – it doesn’t make you safer and just keeps you in the storm for longer.

Stay safe this summer

While you’re enjoying your summer plans, keep lightning safety in mind.

If someone nearby does get hit by lightning, lightning victims don’t hold the electric charge, so call 911 and begin first aid right away. About 90% of lightning victims survive, but they need immediate medical attention.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.