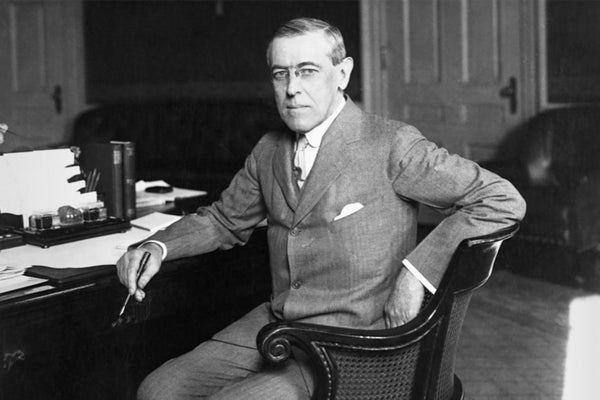

In 1917, President Woodrow Wilson was having trouble ginning up support for the U.S. entry into the Great War. He found it nearly impossible to reach Americans with his message, distracted as they were by the deluge of information coming from movies, radio, telegrams and newspapers.

To cut through his era’s information overload, Wilson authorized roughly 75,000 American volunteers to deliver passionate, four-minute speeches about the U.S. war effort. They were called the Four Minute Men. The moniker came from the length of time it took to change film reels in early movie theaters, where these speeches were delivered. They were the TikToks of their era, delivered live during those brief four minutes between reel changes.

The campaign was effective but controversial. It sparked a heated debate during the Jazz Age about media manipulation, and whether it was ethical to use tricks borrowed from advertising and popular culture to persuade the public. The United States at that time faced a communications crisis very much like our own today. Americans were suffering from conspiracy thinking, information overload, short attention spans—and, with the spread of the 1918 flu, a pandemic that nobody wanted to talk about.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

It’s no wonder that the anxieties from that period have returned, reigniting century-old culture wars over “fake news” and “media elites.”

The Four Minute Men were the brainchild of a former newspaper joke writer named George Creel, who headed the Committee on Public Information (CPI). Writing for Scientific American in 1918, Creel portrayed his team as vanquishers of wartime conspiracy theories, including one false claim of “10,000 Englishmen in Colorado waiting, heavily armed, until all the American forces have gone to France, at which time they will issue from the mountain fastnesses and annex this fair land to the British throne.”

I’m a science journalist who often writes about history, and I researched the backstory of Creel’s approach to propaganda in my book Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind. CPI was one of the first groups to deploy psychological operations, or psyops, on behalf of the U.S. government.

Creel’s work also catalyzed the careers of two of the 20th century’s most influential media analysts, men whose wildly different approaches to the problem helped to shape the chaotic media landscape we find ourselves in today. They were Walter Lippmann, co-founder of The New Republic, prolific author, and crusader for progressive causes; and Edward Bernays, an advertising maven and nephew of Sigmund Freud who became an operative for the C.I.A. in Guatemala during the 1950s, planting misinformation in the press. Both men worked for the U.S. government in World War I, dispensing “public information.” Lippmann produced anti-German fliers for the Army’s Military Intelligence Branch overseas, while Bernays developed influence campaigns on the home front for the CPI. After the war, they decamped to a cultural battlefield, publishing competing books that were thinly veiled commentaries on the CPI’s activities.

At the heart of the Lippmann-Bernays debate was a stark question: Is there truly a line between propaganda and journalism, and should we be worried about it?

Lippmann, who criticized CPI head Creel as “reckless and incompetent,” came out swinging first. In his influential 1922 book Public Opinion, he popularized the word “stereotype” to describe what happens when media operatives simplify world events to make them palatable to audiences with limited time and attention. Disturbed by this stereotyping process, he pushed news media and civil institutions to be as honest as possible with the public about their biases. Lippmann believed that there was a way to segregate propaganda from news, but only if we first acknowledged that prejudices, misinformation and sheer ignorance made the task complex—and, sometimes, impossible.

A year later in 1923, Bernays clapped back with a book called Crystallizing Public Opinion. He suffered no ethical agonies over misleading the public. Indeed, he crowed that a public relations expert could manipulate people on behalf of anyone, “be it a government, a manufacturer of food products, or a railroad system.” His book was laced with stories of his own public relations triumphs, all recounted in a spooky and awkward third person. At one point he described “someone” who ran a public relations campaign for the government of Lithuania. Bernays described the work as “advertising a nation to freedom,” as if good marketing could replace political accountability.

Without ever naming Bernays, Lippmann disparaged the rise of the “publicity man,” whom he excoriated as “censor and propagandist, responsible only to his employers.” His implication was clear: Bernays’s work in PR was a continuation of what he had done for the wartime propaganda machine. Ultimately, Lippmann believed that the “publicity man” was a sign of the times, a professional yapper trained by war to turn every kind of message into a weapon. Perhaps there was a gray area between news and propaganda, Lippmann admitted, but the publicity man was squarely on the side of propaganda. And propaganda was built out of lies.

Bernays fought back like the slick ad man he was, by twisting Lippmann’s ideas, pretending that the journalist was somehow in agreement with him. According to Sue Curry Jansen, a Muhlenberg College communications professor, Bernays told anyone who would listen that “Lippmann provided the theory and [Bernays] provided the practice.” That made it sound like they had been collaborators. But it, too, was a distortion of the truth. Jansen found several letters that Bernays sent Lippmann, asking him to help with the Lithuanian government campaign. Lippmann never gave more than a desultory response.

It was a peculiar, one-sided relationship. Still, it should not be surprising that PR man Bernays played up a non-existent connection with Lippmann, while the media commentator kept his mouth shut rather than feeding the beast. In 1925, Lippmann published another book, The Phantom Public, which critiqued the New York Times’ biased, or “stereotyped,” coverage of the Bolshevik revolution. Bernays published Propaganda in 1928, which celebrated media manipulation as the most “efficient” way to guide the public amid a free market of ideas; a copy of it was later found in the library of Nazi politician Joseph Goebbels.

We may not remember Lippmann and Bernays’s names, but their debate left behind a lingering sense of distrust and fear of what the media is doing to us. We still struggle to extract truth from today’s version of the Four Minute Men, wedging their propaganda into the precious few seconds before the next video begins.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.