Imagine the following scenario. Scientists identify a potential global threat, but initial data are spotty—not enough to spur drastic action. Rapidly, relentlessly, the threat grows. What once was preventable becomes inevitable. The world has no choice but to endure the disaster at the cost of trillions of dollars and millions of lives.

This is the story of COVID pandemic—but it could equally well be the story of a catastrophic strike by a large asteroid. As we emerge from the worst of COVID-19, we should heed this lesson: low-probability, high-impact events do occur; but they can be mitigated if we prepare and act early enough.

Asteroids are like viruses in a sense: they number in the tens of millions but only a few types pose a threat to humans. For asteroids, it’s the “near-Earth” variety—those with orbits that come close to our own—that we must worry about.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Also as with viral outbreaks, the likelihood of a catastrophe is unlikely in any given year, but almost inevitable over time. And just as we can in principle develop vaccines against emerging viruses before they cause too much damage, creating immunity without making people sick, we can similarly use modern technology to develop a level of global immune response to asteroid collisions. But this requires ongoing investments in research and preparedness—and while the U.S. spent more than $6.5 billion dollars on pandemic preparedness over the past decade (with admittedly mixed results), the nation spent less than a tenth of that on the work of asteroid detection and deflection. This is far too low.

In fact, impacts from space happen all the time, but they are generally small and harmless. The Earth is peppered with meteors throughout the year that are mere inches across or less, which burn up as shooting stars when they enter our atmosphere. The threat comes from the bigger ones, which are house-sized or larger. These strike less frequently, but they do happen. In 2013, a 60-foot-diameter meteor exploded over the city of Chelyabinsk, injuring thousands of people. The really big ones—miles across—are even rarer, occurring every few hundred million years or so. But the damage they do can be catastrophic. Think of the mass extinction 65 million years ago that wiped out most of the dinosaurs. The good news is that we’ve found most of those and, fortunately for us, Earth is not in their crosshairs.

But there is a middle ground that demands our attention: “city killer” asteroids that are about around the size of a football field and could unleash 10,000 times the energy of the atomic bomb that leveled Hiroshima. They seem to hit us every few thousand years, on average. There are likely many tens of thousands of them with orbits near Earth’s, yet we’ve only found about one third of these.

And finding them is hard. Even the big ones are tiny, cosmically speaking, and are camouflaged against the blackness of space by their charcoal-like dark surfaces. Ground-based telescopes, which measure reflected light, struggle to see these small, dim objects. Only a few hundred are discovered each year. To significantly improve the rate of detection we need to move off the Earth, to the realm of the asteroids. We need a telescope in space.

The Near-Earth Object (NEO) Surveyor is a modest space telescope currently under consideration by NASA. Instead of looking at reflected light, it would seek out heat signatures of asteroids, which glow with infrared radiation against the cold background of space. And in space, where there’s no bad weather and daytime that limit observations, the NEO Surveyor could find more city-killer asteroids in the next 10 years than have been discovered by all the telescopes on Earth over the past three decades.

The mathematics of orbital mechanics that characterizes asteroids can be as heartless as the exponential growth that goes with viral outbreaks. And as with broad testing regimes that have been used during COVID, a dedicated effort to discover potentially hazardous asteroids will be the key to preventing disaster. It’s possible to alter an incoming asteroid’s orbit to protect the Earth, but that becomes increasingly more difficult depending on how close we are to impact. It is far easier to act years (if not decades) in advance.

After more than a decade in bureaucratic purgatory, where the NEO Surveyor has struggled to gain approval, the project appears ready to move forward. The Biden administration recently proposed to fund this mission in its latest NASA budget; Congress should support this request. It will take years to build and launch, but as early as 2026 we may see the start of the first dedicated effort to understand the scope of the asteroid threat.

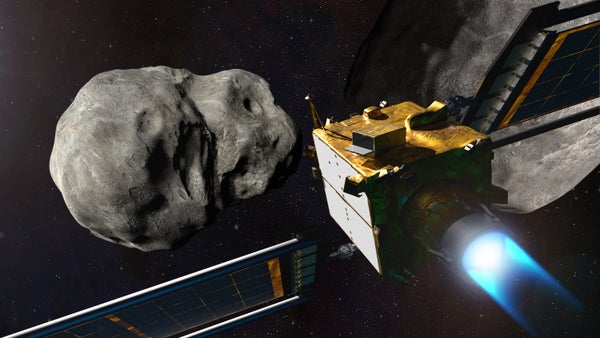

We also need to invest in deflection technology, the “vaccine” of the asteroid response. Fortunately, NASA is close to launching a mission called the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART). In 2022, the spacecraft will ram into the tiny “moon” that orbits the near-Earth asteroid Didymos, slightly changing its orbit. Scientists will compare the exact degree of change to their predictions, which will help them understand how to alter asteroid orbits more effectively in the future. This is only a test, but it could serve the same function as the years of basic research into the field of mRNA vaccines that ultimately paid off when applied to COVID.

We must also continue to support sky surveys by ground telescopes, which can support the work of space-based missions. The Vera Rubin Observatory, for example, now under construction in Chile and especially good at finding fast-moving objects in the solar system, will greatly assist in asteroid detection. (The proposed “megaconstellations” of Earth-orbiting satellites by Amazon, SpaceX, OneWeb, and others threaten to overwhelm our view of these dim objects and make asteroid detections more difficult. There is no easy solution to this, beyond further confirming the need for space-based detectors located in quieter regions of the solar system.)

The coronavirus pandemic has many humbling lessons for humanity. But let this be one of them: low-probability, high-impact disasters do occur; and there is no higher impact disaster than a large asteroid collision with the Earth. We know that early awareness enables early action. Big problems later on can be prevented by small investments now. Let’s not be caught off-guard again.

This is an opinion and analysis article; the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.