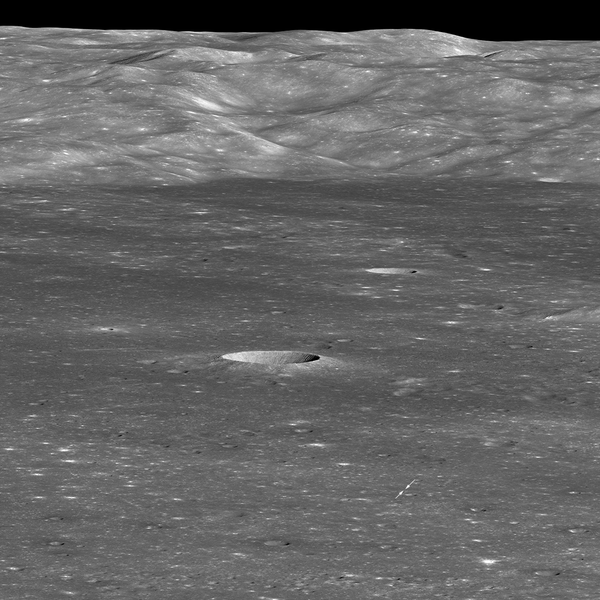

NASA and the China National Space Administration (CNSA) are coordinating efforts focused on the recent touchdown of China’s Chang’e 4 moon lander and Yutu 2 rover on the lunar farside. The robotic probe throttled itself down on January 3 within the Von Kármán Crater in the moon’s South Pole-Aitken Basin.

Newly released images of Chang’e 4’s landing site, snapped by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) on January 30 and released yesterday, were just the first step in a collaboration between the two space agencies. NASA has also held discussions with the CNSA to look for plumes and other debris lofted from the lunar surface by the Chinese probe’s rocket exhaust during the landing.

For that task, an LRO-carried Lyman–Alpha Mapping Project (LAMP) instrument—an ultraviolet-imaging spectrograph—is monitoring the moon’s thin atmosphere and cratered surface for signs of alteration. The intent is to compare any results with theoretical predictions of gas and exhaust plume particle ejecta. Doing so would help space scientists improve their predictions for just how lander propulsion systems will impact the lunar landscape.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

LAMP: Lighting the Way for Cooperation?

LAMP was developed by the Southwest Research Institute. “LRO was not well positioned to see any gas plume emissions at the time of the descent. We took a close look at our LAMP data set to search for any signatures of gases of interest…and confirmed no detections of any residual signals roughly 40 minutes later when we passed nearest the landing site latitude, just on the limb as viewed by LRO on the dayside,” says Southwest’s Kurt Retherford, principal LAMP investigator. “We know that LAMP is capable of detecting such active experiment type gas releases,” he says. “We’ll continue planning these type of LRO LAMP observations coordinated with future landed missions in the next few years ahead in LRO’s next extended mission as best we can.”

Publicly Available Data

NASA and the CNSA have agreed that any significant findings resulting from this coordination activity will be shared with the global research community at the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space meeting in Vienna this month. “All NASA data associated with this activity are publicly available. In accordance with administration and congressional guidance, NASA’s cooperation with China is transparent, reciprocal and mutually beneficial,” space agency officials said in a January 19 Web site posting

Over the past few years NASA has been prohibited from cooperating with China on space activities. That ruling was originally signed into NASA-funding appropriations bills by Rep. Frank Wolf (R–Va.) who chaired the House Appropriations Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies Subcommittee before retiring in 2014.

The final law Wolf put in place—the Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2015, which remains in effect today—states no funds may be spent by NASA to “develop, design, plan, promulgate, implement or execute a bilateral policy, program, order or contract of any kind to participate, collaborate or coordinate bilaterally in any way with China or any Chinese-owned company unless such activities are specifically authorized by law after the date of enactment of this act.”

NASA is able to formally collaborate with China as long as it notifies Congress in advance and gets congressional approval of the specific interaction. But the details of that process for the LRO observations have not yet been publicly released. “So working with China on Chang’e 4 is a one-time, ad hoc thing, not a breakthrough in the relationship,” says political scientist John Logsdon, professor emeritus at The George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute. “But with the Democrats in control of the House, I am guardedly optimistic that the artificial and arbitrary prohibition on NASA interacting with its Chinese counterparts will be lowered.”

Appropriate Certification

Scientific American asked NASA officials how working with China and its Chang’e 4 undertaking was handled. According to a response statement from the space agency’s Office of International and Interagency Relations, “The statutory prohibition on NASA’s use of appropriated funds for bilateral cooperation with China…does not apply to activities that NASA has certified to Congress, [which]do not pose a risk of resulting in the transfer of technology, data or other information with national security or economic security implications to China; and that do not involve knowing interactions with officials who have been determined by the U.S. to have direct involvement with violations of human rights. In accordance with the law, NASA made the appropriate certification to Congress for this activity.”

An additional facet to this unusual collaboration emerged in a South China Morning Post story last month. The newspaper quoted Wu Weiren, chief scientist of China’s lunar program, as saying U.S. space scientists had asked permission to “borrow” China’s Chang’e 4 spacecraft (and its associated Chinese farside relay satellite Queqiao) to plan a mission to the moon’s farside. That overture, according to earlier comments made by Wu on China Central Television, occurred at an international conference a few years ago.

The Queqiao satellite launched last May is now in position to monitor and relay communications from the lunar farside to mission controllers on Earth. Wu said U.S. scientists had asked China to extend the Queqiao relay satellite’s life span and to outfit a U.S.-supplied beacon on the Chang’e 4 mission, to help the U.S. in staging its own lunar-landing strategy. “We asked the Americans why they wanted our relay satellite to operate longer,” Wu told CCTV. “They said, perhaps feeling a little embarrassed, that they wanted to make use of our relay satellite when they make their own mission to the farside of the moon.”

Europe Moves Forward

Meanwhile the European Space Agency has had a long-standing relationship with China’s lunar exploration agenda, says Bernard Foing, executive director of the ESA’s International Lunar Exploration Working Group. Foing was also principal project scientist for SMART 1, the first European mission to the moon. “We collaborated with Chinese scientists on SMART 1 data analysis,” he says. But beyond that, Foing underscores a 2005 collaboration agreement for ESA participation providing ground stations for control and data relay of the Chang’e missions, starting with moon orbiters Chang’e 1 and Chang’e 2 in 2007 and 2010, respectively, as well as the Chang’e 3 spacecraft, which in 2013 conducted China’s first lunar landing. “The Chang’e 4 mission will advance technical maturity for future robotic and human landings,” he notes. “The next step will be Chang’e 5 and Chang’e 6 sample return from the moon. A number of other robotic landers are planned in the upcoming year that could build up, de facto, a lunar robotic village—a precursor to human settlements.”

Indeed, ESA Director General Johann-Dietrich Wörner is promoting what he terms the “Space 4.0” era, an element of which is an international “Moon Village.” Space 4.0 reflects an evolution, he has stated, where space is no longer the preserve of a few spacefaring nations but instead an open and diverse stage for governments worldwide as well as private companies, academia and industry. Whether or not China’s homegrown plans for eventual lunar bases will somehow become part of the ESA’s Moon Village—or vice-versa—remains to be seen.

Exploratory Talks

“ESA is conducting exploratory talks with the China National Space Administration regarding possible European cooperation on the following Chinese moon missions,” says James Carpenter of the ESA’s Directorate of Human and Robotics Exploration. Back in 2017, for example, a joint workshop of the two space agencies on lunar samples was held in Beijing.

Later this year China intends to pursue a sample-return effort to retrieve lunar rocks for analysis on Earth via the country’s Chang’e 5 lunar mission. That prospective outing’s debut depends on the return to flight of the nation’s Long March 5 rocket, however, which suffered a launch failure in July 2017. If successful, the Chang’e 5 mission would be the first lunar sample-return project in over four decades after the former Soviet Union’s Luna 24 mission of 1976.

In the meantime Europe and China could advance a nascent partnership in human spaceflight. Carpenter spotlights the ESA–China intergovernmental framework agreement signed in 2005 as well as a pact signed in 2014 that opens the possibility for the two space agencies to share resources on the ground and in space dedicated to training and actual spaceflight of international human crews. “At the moment, the cooperation on scientific utilization is advancing,” he says. “Discussions have occurred regarding astronaut training, possible flight opportunities for European astronauts as well as the cooperation in the area of infrastructure, but no specific plans have so far been confirmed.” The ESA has also provided Mars environmental data to the CNSA in view of the Chinese Mars mission set for departure in 2020, he adds.

Optimistic Signal

All these collaborative gestures could be seen as positive signs for a new kind of space race—something decidedly different from and friendlier than the rivalry that fueled the cold war–era competition between the Soviet Union and the U.S. in the 1960s. That fierce struggle culminated in the Apollo lunar landings—a spectacular feat that has yet to be repeated after the Apollo program’s cancellation in the early 1970s.

“Apollo showed us that a space race through competition was not sustainable,” says lunar expert Clive Neal, an engineering professor at the University of Notre Dame. “What the International Space Station has showed us is that cooperation is the way to have a long-term, sustainable human presence in space. So any international cooperation in this area [of moon exploration] is a good thing. We should avoid repeating history if we want to expand humanity into the solar system.”