In Hindu folklore, there is an enormous serpent king called Vasuki, who is said to possess supernatural powers and strength. Often depicted as coiled elegantly around the neck of the deity Shiva, Vasuki is one of many snakes worshipped at India’s annual Nag Panchami festival—a practice believed to ensure safety and prosperity in the coming year.

Two researchers who recently discovered a giant snake species—which likely lived 47 million years ago in what is now India’s state of Gujarat and was an estimated 36 to 49 feet long—took inspiration from the legend in naming the species Vasuki indicus. “It is very symbolic,” says Debajit Datta, a postdoctoral fellow at the Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee (IITR) and co-author of a study about the species that was published on Thursday in Science Reports. Vasuki “is our king. And this here, much like him, is an exceptionally large snake.”

V. indicus’ remains were initially recovered from a coal mine in Gujarat almost 20 years ago by Datta’s co-author, IITR paleontology professor Sunil Bajpai. At the time, he believed the fossils belonged to an already known prehistoric species of crocodile, and he stashed them away in his laboratory. It wasn’t until Datta, who joined Bajpai’s lab in 2022, began examining the fossils last summer that the two realized the remains belonged to a different kind of animal. “There’s a whole host of literature describing previously discovered crocodiles,” Datta says. “But when we started chipping away at the sediment around the fossils, we began to see that they had some anatomical features that, in fact, were not crocodilian and instead maybe snakelike.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

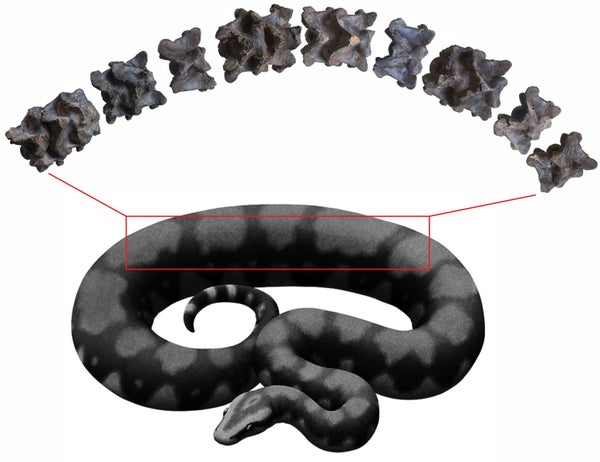

Composite skeleton representing the trunk region of Vasuki.

Sunil Bajpai/Debajit Datta

The researchers cleaned and identified 27 relatively preserved vertebrae, ranging between roughly 1.5 and 2.5 inches long and 2.5 and four inches wide, from what they think was an adult animal. V. indicus may have been one of the biggest snakes of all time, and it belonged to Madtsoiidae, a family of snake species that lived across the Southern Hemisphere, Bajpai says. The species is comparable in size to the also extinct Titanoboa cerrejonensis , which existed an estimated 60 million years ago and is the largest known snake species.

Although the mining area where Bajpai found the fossils is dry and dusty today, it was swampy when V. indicus roamed the Earth, he says. Jesus Rivas, a New Mexico Highlands University biology professor who studies snakes, suspects that V. indicus’ size made maneuvering on land difficult and that the species could move more gracefully through water. “In order to breathe, the snake would’ve needed to lift its rib cage, requiring a very big muscular effort to fight gravity,” says Rivas, who was not involved in the study. “But with [its body] in water, breathing was probably easier. And that’s why many large snakes today, like anacondas, are aquatic.”

The discovery of V. indicus gives scientists not only a closer look into the evolution of snakes but also a deeper understanding of how continents physically shifted over time and species dispersed across the globe. “Sometime, about 50 million years ago, India collided with Asia, and as a result of this collision, a key terrestrial route was created,” Bajpai says. “This is what allowed these snakes and other prehistoric animals to cross over and eventually evolve and establish new species.”