Researchers have discovered an array of fossilized footprints in an ancient sand dune in Gibraltar, the small British territory on the southwestern tip of the Iberian Peninsula. One of the prints, they suggest, may have been made by a Neandertal.

If they are right, the find is highly significant: Only one other Neandertal track site is known, a set of 62,000-year-old footprints from Romania. And the Gibraltar print is reportedly much younger, in which case it could have been made by one of the last Neandertals ever to walk the Earth. But other experts are not so sure about that interpretation. The discovery figures into long-standing questions about when anatomically modern Homo sapiens colonized Europe and when the archaic Neandertals went extinct.

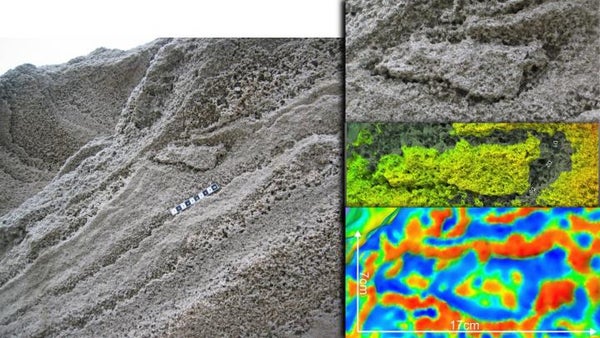

Analysis of the tracks revealed five types of prints in the dune. To identify which animals made them, Fernando Muñiz of the University of Seville in Spain and his colleagues studied the sizes and shapes of the prints, comparing them with other preserved tracks and correlating them with fossilized animal remains found elsewhere in Gibraltar. The tracks appear to come from several kinds of mammals, including elephant, deer and leopard. One of the prints, although poorly preserved, looked decidedly human—the impression revealed a right foot that was wider in the front than in the rear and had five aligned toes. And the size of the print hints it belonged to a young adolescent. But what species of human produced the track?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The print itself records physical characteristics associated with both Neandertals and modern humans—deciding between the two candidates on the basis of the size and shape of the print was impossible. So to zero in on the track maker, the researchers looked to the age and location of the footprint. The team dated the tracks to around 28,000 years ago using a technique known as optically stimulated luminescence, which can determine when sand grains were last exposed to sunlight. Previously researchers, including some members of the footprint team, have argued based on remains found elsewhere in Gibraltar that Neandertals lived in this region at that late date, surviving thousands of years longer there than anywhere else in their formerly extensive range across Eurasia. Ultimately, H. sapiens supplanted Neandertals and other archaic humans around the globe. But our species did not seem to have reached Gibraltar until rather late in the game.

Considering the form of the footprint and the fact it hails from a time when Neandertals—but not modern humans—lived in Gibraltar, the track maker was probably a Neandertal, Muniz and his colleagues conclude. The scientists detail their findings in a paper currently in press at Quaternary Science Reviews.

Their argument has met with mixed reactions from experts not involved in the new study. “Foot proportions [of H. sapiens and Neandertals] are more or less the same, making it really difficult to tell from the contour of a footprint whether a modern human or Neandertal walked on those sandy dunes 28,000 years ago,” notes Jeremy DeSilva of Dartmouth College, an expert on fossil human feet. But given the age the print and where it was found, the suggestion it was made by a Neandertal is “perfectly reasonable,” he says. Paleoanthropologist William Harcourt-Smith of Lehman College, who also specializes in foot anatomy, is more circumspect. “28,000 years ago is right at the twilight of the Neandertals’ existence (as far as we know),” he says. And although modern human remains from this time period have yet to turn up in Gibraltar, they are known from other parts of Europe. “It is possible that a Neandertal might have made [the print], but honestly, from an anatomical perspective, the poor quality of the print makes it very hard to prove either way” he says.

Other experts worry about hanging the attribution of the print on its age. Thomas Higham of the University of Oxford and his colleagues have dated a number of Neandertal and early modern human sites across Europe. In their own attempts to determine the ages of the Neandertal archaeological remains from Gibraltar, they could not replicate the late dates previously obtained for some of that material. And the ages they got for Neandertal leavings from the south of Spain usually turned out to be much older than originally supposed, suggesting the seemingly late survival of Neandertals in southern Iberia was an artifact of the dating method used. Instead, the dates Higham’s team came up with indicated Neandertals everywhere had disappeared by around 39,000 years ago.

Further complicating matters, new evidence suggests modern humans may have reached southern Iberia earlier than previously thought. In a paper published earlier this month in Nature Ecology and Evolution, Miguel Cortes-Sanchez of the University of Seville and his colleagues report on their efforts to date a site in Málaga, Spain, called Bajondillo Cave whose archaeological deposits span the Neandertal–modern human transition. Their results suggest modern humans replaced Neandertals at Bajondillo by around 43,000 years ago. And if moderns were in southern Spain by then, well, Gibraltar is only about 65 miles from Málaga as the crow flies.

All told, “I would be very skeptical of [the 28,000-year-ago date] lending support to a Neanderthal identification in this case,” Higham says of the Gibraltar footprint.