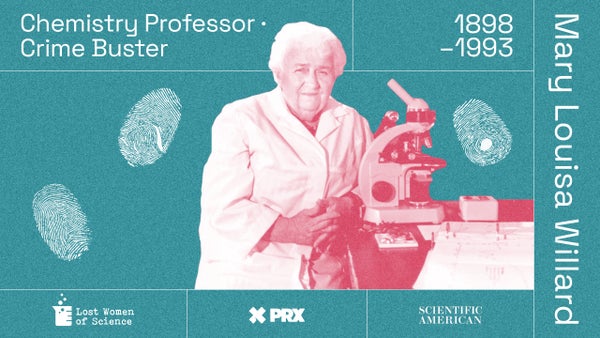

Mary Louisa Willard, a chemistry professor at Pennsylvania State University starting in the late 1920s, was a colorful character. Her hometown of State College, Pa., knew her for stopping traffic in her pink Cadillac to chat with friends and for throwing birthday bashes for her beloved cocker spaniels. Police around the world knew her for her side hustle: using chemistry to help solve crimes.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Lost Women of Science is produced for the ear. Where possible, we recommend listening to the audio for the most accurate representation of what was said.

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Carol Sutton Lewis: Mary Louisa Willard. Or “Lady Sherlock” as one newspaper called her. She was a chemistry professor who picked up a side hustle as a forensic criminologist and soon, she was helping law enforcement investigate everything from forgeries to homicides using the cutting-edge science of her time.

Sarah Wyman is joining me to tell us this story.

Sarah Wyman: Okay, Carol, I want you to picture this scene for me. We’re at Pennsylvania State University in the chemistry building. Dates are murky, but we think it’s sometime in the 1940s, and a woman is walking down the hallway. She is holding a dead chicken.

Marching on either side of her are two police officers. Both of them also holding—you guessed it—dead chickens. And these birds are allegedly victims of murder, and the woman who's being escorted down the hall is their accused killer. She is indignant. She is insisting that she is innocent.

And after a few more steps, she and the policeman reach Room 101. They open the door to find this spacious, sunny laboratory, with shelves and shelves of glass bottles covering the walls. Several different kinds of expensive-looking microscopes are sitting on lab benches. And in the middle of it all, a short, white-haired professor is sitting at a desk, poring over some sheets of paper.

And at this moment, one of the police officers clears his throat. And says, “Dr. Willard, we need your help.”

Carol Sutton Lewis: This is Lost Women of Science. I’m Carol Sutton Lewis. And today, we bring you the story of Mary Louisa Willard. We’ll learn about her astonishing career—how her brilliance in the lab made her a valuable resource to police investigators, how she testified as an expert witness in major criminal trials, and of course, we’ll find out how this chemist cracked the case of the dead chickens.

Carol Sutton Lewis: So, hi Sarah.

Sarah Wyman: Hello!

Carol Sutton Lewis: So, let's back up a minute. How did we get here? I’m assuming chicken murders weren’t her specialty.

Sarah Wyman: Yeah, Mary Willard was first and foremost a professor of chemistry. She did end up having this incredible side hustle solving crimes, and serious crimes too, not just chicken murders, I mean she worked on cases of breaking and entering… homicides… assaults. And we’re going to get to that a little bit later. And her story really begins at Penn State University, which is where she was quite literally born and bred. She was born in a cottage on campus, just a couple hundred yards away from where her lab would one day be. And her family — the Willards — were deeply embedded in Penn State’s history.

J. Peter Willard: My name is James Peter Willard and, and Mary Willard or ML Willard was my aunt.

James Peter Willard mostly goes by Peter. He lives in New York State now, but he grew up in State College, not far away from his aunt. And I called him a few weeks ago to get as much good intel about his aunt as I possibly could. And let's just say, Peter is not a man prone to hyperbole.

Sarah Wyman: I've read about your aunt. Um, the word gregarious comes up a lot, but how do you remember her personality as a kid? What was she like to be around?

J. Peter Willard: Normal.

Sarah Wyman: Normal!

J. Peter Willard: She was very normal. She was very normal with us.

Sarah Wyman: Yeah.

Peter: I would never say that she was thinking she's a big deal or something like that. That— that sort of thing never showed up.

Sarah Wyman: I was surprised by this answer, Carol. I mean, I'd been reading a lot about Mary at this point, and normal is one of the last words that would come to my mind.

I mean, I've been digging up these old profiles of her, and even in her obituary in the local paper, there were half a dozen people interviewed and most of them had a hysterical memory to share about her.

Lots of them mentioned her car—this legendary pink Cadillac— and also how she drove it. Someone said that Mary had to look through the steering wheel instead of above it because she was only about five feet tall. Someone else said that when you saw her driving down the street, she'd stop in the middle of the road if she saw somebody that she knew and completely hold up traffic to catch up with a friend.

She had a whole litany of interesting collections and hobbies. Like, her rose garden where she was growing 96 different rose species.

Rumor has it that she also once grew marijuana in her garden for police experimenters?

Carol Sutton Lewis: Of course it was for police experimenters.

Sarah Wyman: [laughs] For research only.

And she never married, and she never had kids, but what she did have were Cocker Spaniels.

J. Peter Willard: That she absolutely loved. She had birthday parties for them. And really the whole neighborhood came. You know, next-door neighbors all the way up and down the street.

Carol Sutton Lewis: She sounds like she's pretty fun, but what do we know about Aunt Mary the scientist? She was a chemistry professor, right? All the way back in the late 1920s?

Sarah Wyman: Yeah, which I realize might seem surprising on its face. I mean, it certainly wasn't extremely common for women to be working in the faculty in chemistry departments at universities during this time.

But Mary came from an academic family. So as I mentioned before, she grew up on Penn State's campus back when the surrounding area was mostly open fields. And her father was a math professor at the university. His name was Joseph Moody Willard. There’s actually a building named after him on campus today.

And back when Mary was growing up, the Willards would host students who needed housing. Visiting lecturers who were coming to the campus would sometimes stay with them too. And so the Willard kids really grew up in this really intellectually stimulating environment.

Carol Sutton Lewis: So, coming from this academic family, I would imagine they were fine, excited, happy about her going to college?

Sarah Wyman: Yeah, Mary didn't talk a lot or write about the fact that she went to college, but according to her nephew, it really would have been like a non event in the Willard family. In 1921, she became one of three women to graduate from Penn State with a bachelor’s in chemistry.

She went on to get a master’s, and then a PhD in organic chemistry from Cornell. And after she returned to Penn State in 1927, she became one of four women teaching in the chemistry and chemical agriculture departments, which you know, not great by today’s standards, but honestly pretty huge at the time! To have four women teaching in those departments. But within the Willard family, this was apparently not a big deal.

J. Peter Willard: I never heard once in the whole time that I was, was, uh, growing up that women, all women didn't have PhDs. That was normal, you don't discuss it. I mean, it's not a big deal.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Ooh, love that.

Sarah Wyman: Yeah, just very very normal. But just to get another perspective on it, I spoke with Bill Herron. Before Bill retired, he taught chemistry at Newman University in Pennsylvania. Now he volunteers as a forensics consultant for the Delaware Innocence Project. And he says… you know that expression that, as a woman, you often have to be twice as good as a man to get half as far?

Bill Herron: …When Willard did this, it was more like 10x.

She had to be just freaking brilliant. I mean, there's just to compete at that time, she was, you know, uh, pardon my French, but she was a serious badass. I mean, you know, she, I mean, there's just no other way to get around it.

Carol Sutton Lewis: So, what was the focus of Mary's chemistry research?

Sarah Wyman: So when she was getting her master's and Ph.D., she became really interested in microscopy, which in its most basic form is just looking at the physical properties of something under a microscope. But Mary was also rapidly becoming an expert in chemical microscopy.

Bill Herron: Chemical microscopy is you're using the microscope as a stage and you are potentially looking at the chemical and physical properties of whatever little dust speck you have there.

Sarah Wyman: That could mean, for example, adding chemicals to a sample on a microscope’s stage… and then watching to see how it reacts.

Bill Herron: You're doing it on the microscope stage with a little teeny weeny pipette. And apparently you don't get to drink coffee because you, you know, you, you know, if you shake, man, it's all over the place.

Sarah Wyman: And you can use this process, of observing these chemical reactions in super fine detail, to actually work out what substances — what elements — make up a sample.

Which, as you might imagine, could come in pretty handy if you were trying to conduct forensics.

Carol Sutton Lewis: And now I know in this day and age, there are a few people who don't know what forensics is because they watch all the crime shows, but can you just tell us, again, exactly what forensics means?

Sarah Wyman: Yeah, so forensics is basically just applying a scientific discipline or scientific tests in order to solve crime. And today, you know, we've all heard of crime scene investigations. But back in the 1920s, this was really not happening in the way that it's happening today.

Bruce Goldfarb: Forensics is actually quite old. I mean, you can go way, way back to, the pyramids, way back to the code of Hammurabi

Sarah Wyman: Bruce Goldfarb is an author who has written about the history of forensic science in the United States.

Bruce Goldfarb: But it's not until fairly recently that there have been sort of the scientific tools to do it in a really scientifically valid way.

Sarah Wyman: Bruce says that there was a turning point for how death investigations worked in the U.S., and it came right around the end of World War I, right around this time when Mary Willard was an undergrad at Penn State.

So, up until this point, the vast majority of death investigations were being carried out by coroners, so coroners would make a judgment call about whether or not they thought somebody had died of natural causes or was murdered, and then after that they'd call in a jury of adults— so laypeople—to vote on whether this was a murder or not. This was called a coroner’s inquest.

Bruce Goldfarb: The original way of doing it is basically crowdsourcing, death investigations. And then, in the late 1800s, 1877, there is a medical model that emerged, first in Boston. They had the first medical examiner, a doctor, put in charge of doing that death investigation.

Sarah Wyman: But even after that medical examiner started working in Boston, most of the country was still on the coroner system. So most death investigations were still being “eyeballed” rather than scientifically investigated.

But when World War I ended, Bruce says a couple of important things had happened. First of all, the war had produced some major technical advances.

Bruce Goldfarb: There is a lot of research in nerve glasses so there are military applications. So they're looking at the chemistry and the effects on the body. And these things grow out of that.

Sarah Wyman: All this led up to 1918, when the first ever forensic toxicology laboratory opened in the United States. In New York City.

Bruce Goldfarb: It was really very, very, very new at that time. And for a long time, they were it.

Sarah Wyman: By 1930, there were still very few cities in the US with medical examiners: the big ones included New York, Newark, New Jersey, and Boston. Los Angeles had also opened a crime lab. But if you were a police investigator in need of a scientist to investigate a murder, you didn’t have a ton of options.

Bruce Goldfarb: I mean, the fact is that at that time there were very, very few people throughout the country with that kind of expertise. It was an emerging field, and there just weren't that many people who were capable of answering that kind of question.

Sarah Wyman: But one of the people who could… was Mary Willard.

Bruce Goldfarb: she was really, in the right place at the right time.

Sarah Wyman: In 1930, Mary Willard was working as an assistant professor at Penn State. She’d started to make a name for herself in microscopy, especially being an expert in analyzing the chemical structure of food and drugs.

And in the meantime, prohibition had created a new need for forensic toxicologists. Bootleg alcohol was often contaminated with poisons. Methanol, or methyl alcohol, was a common one. But there were others too.

Bruce Goldfarb: God knows what gasoline, you know, just to dilute a little bit and give it some kick, you know, just to, I don't know, just like, you know, you buy some, you buy some little glassine envelope from a street. You have no idea what's really in it.

Sarah Wyman: So, law enforcement had their work cut out for them. They had to figure out what was causing all of these poisonings, and then hopefully they could use that information to trace the tainted samples back to the bootleggers who were responsible.

But in order to do that, they needed someone who could separate the substances in contraband alcohol samples and perform a chemical analysis to identify them. Which is why, in 1930, Mary Willard was tapped by some Pennsylvania revenue officers to do just that.

There isn’t a detailed record of the first case that Mary worked on, but she must have done a good job because shortly thereafter, a judge in Scranton got in touch with another case, and before long, Mary’s phone was ringing almost every day with requests for chemical analyses on everything from paint to bloodstains, drugs, and poisons.

Bruce Goldfarb: That sort of thing does not surprise me at all that people would seek her out from all over the place because, you know, she was one of the very, very few independent people, who was capable of doing such a thing.

Sarah Wyman: Over and over again, Mary was called upon to help solve homicides, arsons, forgeries, and then one day, a woman walked into her lab in tears, protesting that she had not killed those chickens. After the break.

[AD BREAK]

Carol Sutton Lewis: You may not know this about me, but over the course of the pandemic, I became obsessed with crime shows. A lot of British crime shows because they're really good at it. And as I'm listening to Mary, it's sort of oh my gosh. It's, it's a classic this little woman you said she was really short and she's driving a car that she has to look through the steering wheel and she's giving birthday parties for dogs. And yet in that lab, nobody's messing with her. She's in that lab. She is solving the cases. She is giving them the evidence they need. Ah, it's so perfect. I mean—

Sarah Wyman: This is so true. She's a regular Doc Martin is his name, right?

Carol Sutton Lewis: Oh my goodness.

Sarah Wyman: She's a regular Father Brown.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Okay. Okay. No, wait, wait, wait. Now you're diving into my territory. She's actually a little more like Vera, if we're going down that road.

Sarah Wyman: It's so true. I mean, the more I learned about Mary, the more shocked I felt that there hasn't been, a book or a Hollywood movie or a British TV show about this woman. But as her nephew Peter puts it, Mary was so unassuming, so normal.

J. Peter Willard: The only time I ever saw something that I thought was abnormal, I was in her house and she was out. I was there alone, and I opened the refrigerator door, and there was a human arm in the refrigerator. It wasn't even wrapped up.

Sarah Wyman: I tried to ask follow up questions, Carol. I really did.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Okay, well, no more words.

[Both laugh]

Sarah Wyman: And the other thing Peter said is that his aunt didn’t really talk about her criminal cases. Except, I found, with one notable exception. The case of the dead chickens.

It all started when 28 of a local farmer’s chickens suddenly dropped dead. The farmer was quick to blame his neighbor, a widow who apparently he’d overheard saying she’d kill the birds if they trespassed in her garden. But the woman insisted she was innocent.

So Mary got to work in the lab. First thing, she would have ruled out a violent death. No external injuries on the birds. So the cause of death was more likely some kind of poisoning. And this is where Bill Herron says Mary would probably have used chemical microscopy. She’d start by taking a sample from the birds’ stomachs.

Bill Herron: And what she’s first gonna do is add some hydrochloric acid.

Sarah Wyman: If the sample contained any silver, mercury, or lead, Mary would be able to see those fall out of the liquid solution.

Bill Herron: It's almost as if you have, like, a hedge maze and you can get lost in the hedge maze. But what you're going to do is by adding different chemicals, you're going to actually wipe out different sections of the hedge until you close the box around what it is. It's kind of like a chemical 20 questions.

Sarah Wyman: But so far, no dice. So Mary would have moved on to chemical question #2. She’d add hydrogen sulfide to the sample.

Bill Herron: And in that case, you kick out copper, bismuth, cadmium, lead, mercury, tin, antimony, and arsenic...

Sarah Wyman: At this point, Mary would have seen some heavy metals precipitate out of the sample. But she still didn’t know which exactly one of those metals was in her sample. So, she’d collect the metals, dissolve them again…

Bill Herron: and then wipe out each one of these in turn by adding and subtracting various things. That particular scheme, I can show it to you, but I can't recite that by heart. And this is what I'm telling you. This, this woman, I mean, it was like having encyclopedic knowledge at her fingertips. And heavy metals are the easy stuff. When you get into other chemicals, there's millions of pathways. And so having that on the tip of your tongue and just doing it, it's magic!

Sarah Wyman: Eventually, Mary narrowed the sample down to arsenic. That’s what killed the birds. But what they did not know is where that arsenic came from. They went back to the scene of the crime, and collected paint samples from a billboard near the farmer’s field. Took those back to the lab, ran more tests, and sure enough: the glue on the billboard came back positive for arsenic. So Mary concluded that these birds were not murdered. They just had a little snack of a billboard, ingested some arsenic, and the neighbor was exonerated.

So this is an example of one case that we know a fair bit about. But there were many, many, many different cases, most of them involving human victims. And Mary was a little bit of a generalist within her field. You know, she could do everything from toxicology - identifying poisons, to a spectrographic analysis of paint, which you might use to check if two paint chips matched, for example.

She didn’t invent all the techniques or instruments she used in her investigations. But she was one of the first people to apply them to forensic science — so in other words, using this technology, this chemistry known-how, in order to solve crimes.

At the height of her career, Mary Willard was serving as an expert witness in court about once a month. She helped out with investigations with every single county in Pennsylvania, and eventually branched out to other states in the US and even worked internationally.

Carol Sutton Lewis: So, at this point, was Mary investigating crimes full time, or was she still teaching at Penn State?

Sarah Wyman: Not only was she still teaching at Penn State, she was working most of these cases pro bono.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Wow.

Sarah Wyman: And on her departmental paperwork. She really framed her criminology work as a hobby. She'd write it down next to, like, collecting vintage roadmaps is like a fun fact. And it's not that her casework was a big secret, necessarily, I mean people knew about it. But she definitely wasn't walking around gloating to her friends and family about, you know, this objectively very cool job. And there may have been another reason for that. Not all of the cases that she was working were quaint countryside chicken mysteries.

She testified in a couple of really pretty major murder trials in Pennsylvania.

One of them was in 1953. A man named Dan Bolish, who was in his early 40s and a much younger friend of his — who was only 17-years-old — were hired to set fire to a building in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Allegedly to collect the insurance money when it burned down. But the 17-year-old was trapped inside after they set the fire, and he later died from the burns he sustained.

So Mary Willard and her lab were called in to help investigate the case. When the case went to trial, Mary took the stand as an expert witness. And there is a whole article about this in Scranton’s Tribune just dedicated to Mary’s testimony. The reporter is obviously tickled by the fact that she’s a woman. They call her “woman criminologist” and “lady scientist” throughout the piece, you know, just in case we’ve forgotten we’re talking about a she-chemist here. And the reporter wrote that Dr. Willard “spoke in a clear voice, enunciating her words precisely—like a professor in a lecture hall.” (Which you know, she literally was a professor, so maybe not that surprising).

But anyway, at the trial, it sounds like she walked the jury through every little scrap of physical evidence the police found and how she analyzed it. And a big part of that was her analysis of kerosene samples that had been taken from the crime scene, Bolish’s car, and a gas station nearby.

In order to compare these samples, Mary used a technique called gas chromatography. Bill Herron says the technology has advanced a lot since Mary’s heyday, but the basic concept is the same. You take your mystery sample, vaporize it, and run it through a long tube with a detector at the end of it.

Bill Herron: It's a lot like a footrace. You're introducing a volatile species down a very thin tube that is, for lack of a better description, sticky. And so, lighter things go through that faster. Heavier things go through it slower. And then you have, like a detector. And so, if you record who comes through at what time, you not only have how long did it take to get through the column, but how much is there.

Sarah Wyman: And you get a graph with peaks of different sizes, depending on how fast each compound traveled through the tube, and how much was in the sample. And so if you look at your graph, you can figure out what your mystery sample is. Like if it’s kerosene. Or even what kind of kerosene.

Bill Herron: Kerosene is not one thing. Kerosene is a vague group of compounds that all boil at approximately the same temperature. It's not like you get the same kerosene every time you go to the gas station.

It's whatever was freaking cheap that week. And so every gasoline station and even, if they come with new kerosene the week after, it's gonna look different.

And in this case, Mary found a match. All three samples showed the same concentrations for all of the different compounds. Connecting the kerosene in Bolish’s car to the scene of the crime.

Bolish was ultimately convicted not just of arson — for starting the fire — but of murder. Since the 17-year-old had died as a result. Dan Bolish was sentenced to death. But then he won a second trial where his sentence was reduced to life in prison. And eventually he died in prison at the age of 59.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Do, Sarah, do we know how Mary felt about the fact that her testimony was putting people in prison? I mean, she's a scientist first and foremost, and in this case, her testimony was helping to decide whether a man was going to get the death penalty.

Sarah Wyman: Yeah, it's not something that Mary wrote about, but we did ask Bill Herron this question.

Bill Herron: I can't answer for her. I can answer for myself. I do hear a lot of people saying, you know, just the facts, ma'am. I mean, for myself, I technically do this full time, but I probably only work three, four hours a day.

The reason is if I start working five, six, seven hours a day, I can't sleep at night. Go to a Game of Thrones reference, you know, a forensic scientist, they're the watchers on the wall. They guard against the White Walkers so everybody else doesn't have to. And it messes with you, it takes you in really dark places because you're always looking at someone's worst day.

And so, the idea that it didn't bother her… I can believe that she didn't talk about it, because you bottle it up. But the idea that it doesn't, that doesn't mess with your head and impact you, I think that's nonsense. If you are wrong, you are either going to send an innocent person to jail or release a guilty person. I can't picture that doesn't weigh on people.

Sarah Wyman: And I would love to know what Mary thought about all this, but unfortunately, I haven’t been able to dig up any records that give us insight. I do know she was really concerned with improving the overall process, especially how evidence was collected.

I mean she would go on lecture circuits around the country, talking about criminology. And in those lectures, she said that more police officers should be getting college degrees in the sciences. She felt that it was so important that the people who were collecting the evidence and responsible for preserving it, for transporting it at the right temperature—she was like, these people need to know that their ability to collect this evidence determines my ability to process it fairly and effectively.

She pointed out that that goes for lawyers, juries and judges, too. Um, it was kind of a pet peeve of hers that in court, she noticed that the kind of subjective tactile exhibits were the ones that juries would really lock onto. So, you know, for example, if you show them a plaster cast of a crowbar dent in a window and then hold up the crowbar and say, look, it fits, everybody's nodding along. But if you start explaining a chemical analysis in super high detail, you can see their eyes glaze over. And she once said of explaining her findings to a jury that usually it has to be done in a colorful Dick Tracy sort of way, but still retaining the basic fundamentals. Much work can be done in this direction.

Carol Sutton Lewis: I just have to note for some of our younger listeners that Dick Tracy reference. Sarah, I don't even know if you're old enough to remember Dick Tracy, but he was a famous cartoon detective. He was in the comics when comics were printed in newspapers, all these, all these ancient concepts.

Sarah Wyman: A newspaper? What's a newspaper, Carol?

Carol Sutton Lewis: But, but I, I say this in jest. I mean, I don't want to take anything away from the seriousness of this, of what Mary was talking about. She makes a really good point.

Sarah Wyman: Yeah.

Carol Sutton Lewis: So, Sarah, we have learned so much about Mary. She's had such a wide ranging career. Now, what do you see as her main legacy?

Sarah Wyman: Well, you know, the crime busting stuff is the obvious place to start. I mean, she was really respected by her colleagues in law enforcement. The police officer she worked with chose her as an honorary member of the Fraternal Order of Police in Pennsylvania, and I know that that was something that she was proud of.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Huh.

Sarah Wyman: She continued to work on cases for a long time after she retired as a professor at Penn State, and she was a well known figure in local courtrooms. You know, she just absolutely did not rest, but I think If Mary were here to answer this question, she would probably want me to talk more about her work as an educator at Penn State. And I say that because it's something she talked about a lot. I read a speech where she was introducing herself at a conference. And the first thing she talked about in that speech was how proud she was to be a professor. Even after she retired, she was holding office hours at age 81 on Penn State's campus. And she made a really big impression on her nephews too. Peter told me something that really stuck with me.

Sarah Wyman: One thing I wanted to ask you about was, you said, in an email that—and I'm quoting you here—that “my aunt was a force for good for whatever she undertook,” and when I read that, I caught my breath, like, that's, that's just such a beautiful compliment. What made you say that, and, and how did you see that in the life that she lived?

Peter Willard: Every moment that I saw her that appeared to me to be the case. It was a very, it was an emotional statement for me to write. There was always a feeling of do what's good and everything will be alright with her. And that goes all the way to her pink Cadillac and her dogs and everything else.

Sarah Wyman: Mary Louisa Willard doesn’t have a building named after her on Penn State’s campus like her dad does. But in 2009, one of her former students, who has since passed away, endowed a scholarship in her name. And the way he talked about her was really beautiful. He said, I liked Dr. Willard as a teacher and as a person. She always made time for you, giving you her complete attention. Dr. Willard was so much more than just a professor.

Carol Sutton Lewis: This episode of Lost Women of Science was hosted by me, Carol Sutton Lewis.

Sarah Wyman: And me, Sarah Wyman. I wrote and produced this episode with help from our senior producer, Elah Feder. I want to thank the American Chemical Society, Penn State Chemistry Department, Dan Sykes, Sue Barr, and Linda Del Monaco Willard.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Lizzie Younan composes all of our music. We had fact-checking help from Lexi Atiya. Hans Hsu sound designed and mastered this episode. Our executive producers are Katie Hafner and Amy Scharf. Our senior managing producer is Deborah Unger. Thanks to Jeff DelViscio at our publishing partner, Scientific American.

Further Reading

18 Tiny Deaths: The Untold Story of Frances Glessner Lee and the Invention of Modern Forensics, by Bruce Goldfarb. Sourcebooks, 2020

OCME: Life in America’s Top Forensic Medical Center, by Bruce Goldfarb. Steerforth Press, 2023

Labors & Legacies: The Chemists of Penn State 1855–1947, by Kristen A. Yarmey. Pennsylvania State University, 2006. See pages 109–110 and 149–150

“Penn State Alumnus Endows Mary Willard Trustee Scholarship.” Pennsylvania State University, April 21, 2009