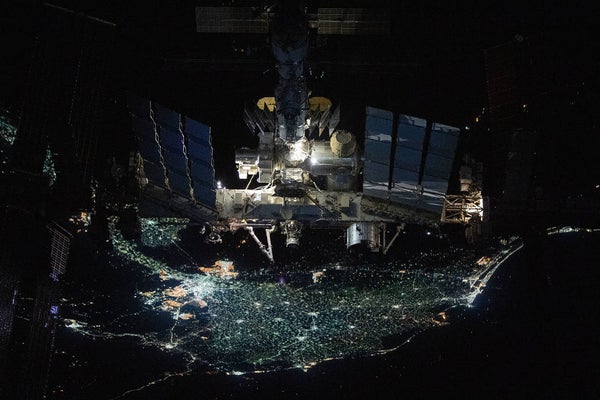

The International Space Station’s final nine years are going to be busy.

NASA just released a report outlining the big-picture goals for the rest of the orbiting lab’s operational life, which is expected to end with a controlled deorbit in January 2031.

These goals are: enabling deep-space exploration, conducting research to benefit humanity, inspiring our species to greater heights, leading and encouraging international cooperation and helping the U.S. private spaceflight industry gain more momentum.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“The International Space Station is entering its third and most productive decade as a groundbreaking scientific platform in microgravity,” Robyn Gatens, director of the International Space Station at NASA headquarters, said in a statement Monday (Jan. 31). (The orbiting lab has hosted rotating astronaut crews continuously since November 2000.)

“This third decade is one of results, building on our successful global partnership to verify exploration and human research technologies to support deep space exploration, continue to return medical and environmental benefits to humanity, and lay the groundwork for a commercial future in low-Earth orbit,” Gatens added. “We look forward to maximizing these returns from the space station through 2030 while planning for transition to commercial space destinations that will follow.”

NASA has been laying the groundwork for that transition for some time now. For example, in December 2021, the agency awarded a total of $415 million to three companies—Blue Origin, Nanoracks and Northrop Grumman—that are leading efforts to build private space stations in Earth orbit.

NASA also holds a separate agreement with Houston-based company Axiom Space, which will launch multiple modules to the International Space Station (ISS) starting in late 2024. These modules will eventually detach from the orbiting lab, forming a privately operated “free flyer” in orbit.

The agency has said that it wants at least one of these private outposts to be up and running before the ISS is decommissioned, so that there’s no gap in orbital research. Such work is needed to prepare for ambitious efforts like a crewed missions to Mars, which NASA aims to pull off in the 2030s.

NASA’s agreements with Blue Origin, Nanoracks, Northrop Grumman and Axiom represent the first phase of a planned two-phase effort to spur the development of commercial low-Earth orbit destinations (CLD) during the 2020s, according to the new 24-page document, which is called “International Space Station Transition Report.”

“The first phase is expected to continue through 2025,” the report states. “For the second phase of NASA’s approach to a transition toward CLDs, the agency intends to certify for NASA crewmember use CLDs from these and potential other entrants, and ultimately, purchase services from destination providers for crew to use when available.”

The second phase in this plan will be similar to the approach NASA has taken with private crew transportation services to and from the ISS, according to the report. In 2014, the agency awarded multibillion-dollar contracts to both SpaceX and Boeing. SpaceX has gotten up and running, launching multiple crewed missions to and from orbit with its Falcon 9 rocket and Crew Dragon capsule since May 2020. Boeing still needs to ace an uncrewed test flight to the ISS before its CST-100 Starliner can carry astronauts.

The switch from the ISS to commercial outposts will end up saving NASA considerable amounts of money, which the agency can put toward deep-space exploration projects, the report notes.

“This savings is estimated to be approximately $1.3 billion in 2031, ramping up to $1.8 billion by 2033,” the report states.

Copyright 2022 Space.com, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.